My friend Dan Ausbury provoked my thought processes by contributing a couple of articles from the New York Times published in the past weeks. The first is “Lecture me. Really.”; the second is “Schools for Wisdom”. I believe they are very much connected and I just want to discuss here some common themes, which are also relevant to my teaching job and my research on the mythologies of teaching and learning (the Zen of Teaching). “Lecture me” by Molly Worthen talks about the validity of using large lectures for courses. It argues that lectures are essential for teaching the humanities’ most basic skills, that is comprehension and reasoning. First of all I believe that these skills are not limited to the humanities but also are of high interest in the sciences and other disciplines and in the development of a whole human being. However the article puts forward some nice arguments in favor of lectures that are good besides being somehow a bit prejudiced towards the humanities and against other subjects. I strongly believe one ought not to divide human knowledge and pursuits into categories, especially when tackling a wicked theme like education.

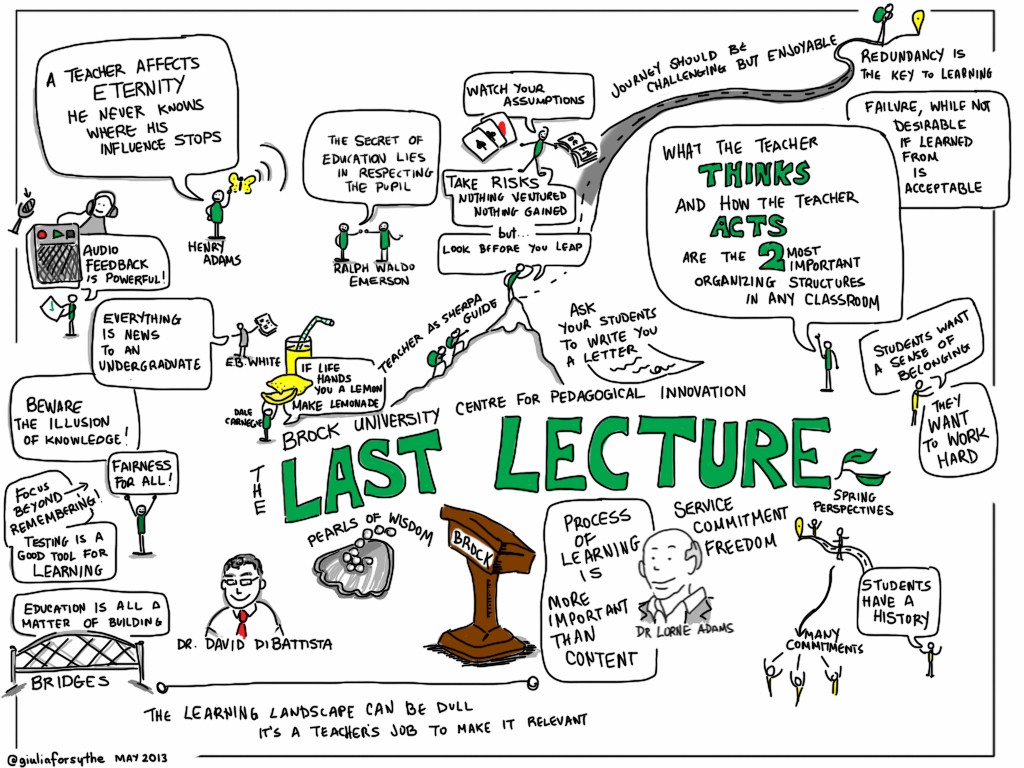

Image by Giulia Forsythe, CC-licensed.

The author of the first paper states that first of all lectures help develop the hard-earning skill of absorbing a long and complex argument for which students are required to synthesize, organize and react to what they are listening to. I italicized the word “absorbing” because it is so revealing of the myth-pattern of objectifying knowledge and the process of teaching with the behaviorist metaphor of “absorption” of knowledge from source to final-destination/brain.

Secondly the author says that the art of taking notes is also a very important cognitive experience for young people and it must be taught so professors should teach and enforce exercises in note taking. Also, he states that note-taking may be a very good exercise for developing mindfulness and attention building. Another point I agree fully with is that lecturing is not a passive learning experience and cannot be replicated by watching videotaped lectures online. That’s a very interesting point because of course there are a lot of video tutorials that may be concealed to be a replacement for lectures but are actually only a substitute lacking interaction and offering the comfort of rewind and pause to hide those skills which are not being nurtured or developed.

In the end, this first article “Lecture me” gives us a good refreshing look at another myth of technologies in education: the lecture being one such method, proven and tried for a long time and now exposed to shame. That it needs not be the only technology or methodology in the game of academic teaching does not means it must be wiped off. Yes, I am aware of the Camus quote:

The danger of lectures is that they create the illusion of teaching for teachers, and the illusion of learning for learners.

But I believe only that this happens precisely when you linger on the myth that lectures produce learning. Learning of discipline-specific knowledge. If you eliminate that, and concede that you have other sorts of learning, but very little learning of discipline knowledge, then there’s no problem with lectures!

The second article, “Schools for Wisdom” by David Brooks shows something very interesting regarding a close subject: what it means to change the classic “content-driven” teaching methodology in favor of discussions or other techniques. First, the article reminds me of a TEDx presentation Gardner Campbell did here at Sagrado Corazón in 2013, with the appropriate title of “Wisdom As A Learning Outcome”. This is after all what education -even university education- is all about: producing wise people (assessment notwithstanding).

Brooks says, if you want to put emphasis on wisdom you have to follow a number of stages. Let’s see them, but first let’s pause a moment to reflect on the bottom line: to have meaningful discussions or group-based collaborations or critical thinking, first one must own (meaning master, up to a certain extent) the knowledge domain. So, there really is a “dictatorship of content”. The point is, in my opinion, not to fall and let it govern our educational endeavors.

Now, on with the stages: First there is basic factual acquisition. This is the stage when one begins with acquiring a little information on a subject. Most often it makes little sense. To have it make sense, the second stage is much needed: pattern formation helps linking facts together in meaningful ways. The information is disconnected to what we already know: thus pattern formation through information navigation helps find meaning, and this is quite similar to what George Siemens postulates in his connectivist theory of knowledge. Third stage is the mental reformation which happens when we begin acquiring the vocabulary of the language of the field and almost of a sudden, things begin to make sense.

At this point information has been transformed into knowledge and it’s alive and this is a very very important point which we want all students to get to in the end. After you live and progress for a number of years with this awareness and your mental identity of the disciplines you’re working with, then you get wisdom. So this article clarifies that knowledge and wisdom are based “on the foundations of factual acquisition and cultural literacy”, which are then essential to the development of learning. This is unfortunately not what some newest education practices posit.

The two articles together show the importance of thinking with our own minds regarding lectures or traditional teaching techniques because both are able to form young minds into developing thinking skills and into developing a mental model of the world and the domains they’re studying. I enjoyed reading them very much.